VICKY SHICK’S “EVERYTHING YOU SEE” AT AMERICAN DANCE INSTITUTE, ROCKVILLE, MD.

Sept. 19-20, 2014

By Luella Christopher, Ph.D.

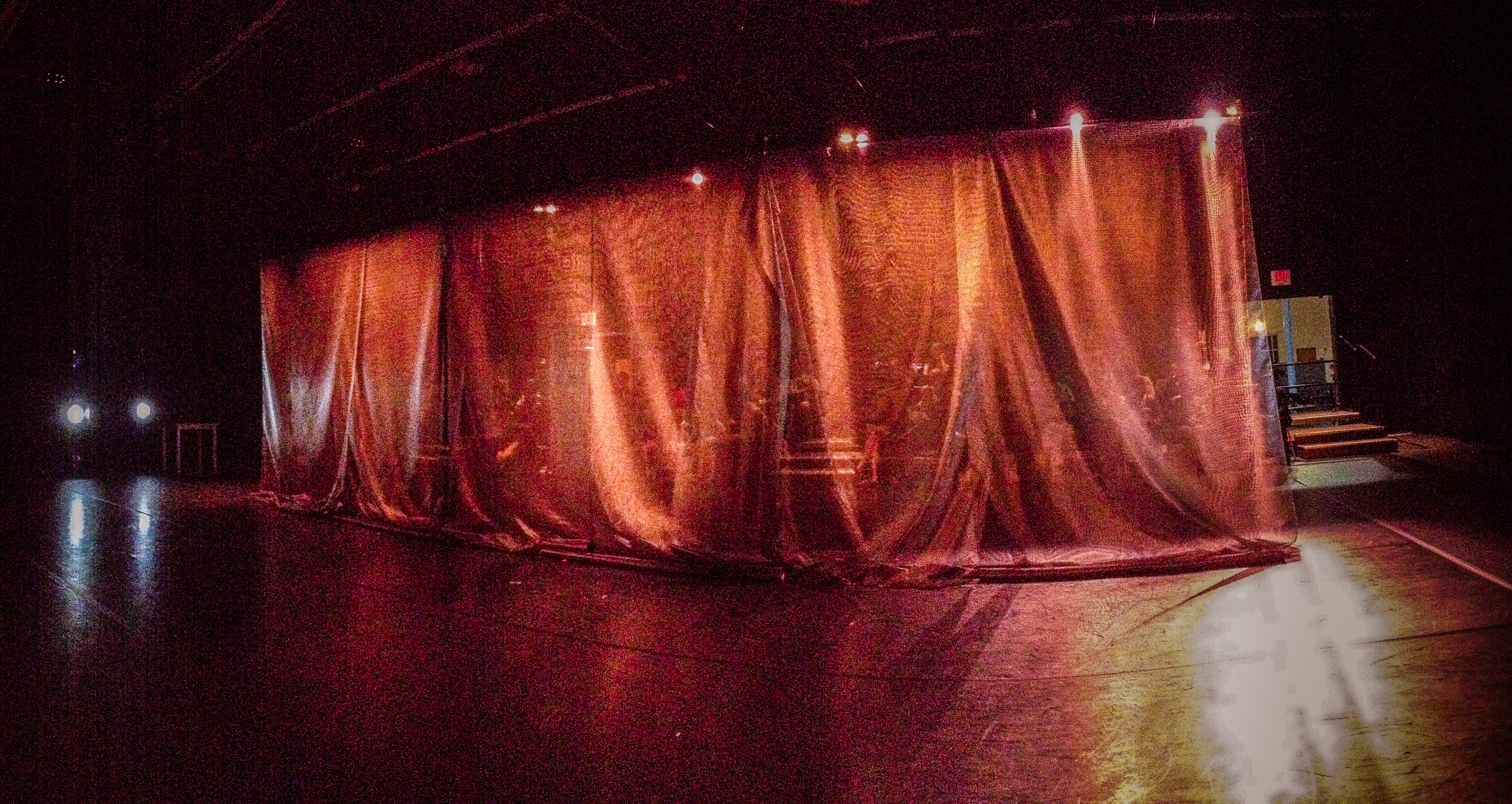

Grandstanding, disconnected, confrontational, or lost in personal reverie? These are just a few of the actions and emotions suggested by Vicky Shick’s dancers in “Everything You See”. The proscenium format promotes a wide array of them. Like the work’s earlier showing at the Joyce Theater in New York City, the audience is seated in two halves on opposite sides of the room. The dancers perform in an expanded rectangle divided by a transparent mesh scrim so that each half of the audience readily sees the dancing on its own side of the curtain though less of what transpires on the far side. Deftly lit by Carol Mullins, it’s technicolor for the side you’re on versus sepia for the side you do not occupy, rendering the movement on the far side more like backdrop or possibly memory.

Eleven dancers move freely from one side to the other, rounding the scrim at its extremities, but there’s no sense of any individual’s enduring story. Many of the movements are performed in solitary. When pairs, trios or larger groups do form, these chance encounters amount to little more than distractions. Indeed, one dancer (Heather Olson) dressed whimsically in coarse fabric with nautical holes flips the bird with both hands as she moves away from her momentary companion. Eyes gaze at one another in the occasional moments of partnering but seem to stare past without really seeing. A peck on the cheek seems like a half-hearted stab at intimacy.

At one point when the sound score replicates traffic sounds, the two male dancers (Levi Gonzalez and Jon Kinzel) could well be expressing a little road rage, one of the few suggestions of a possible narrative. A particularly strong dancer in huge skirt with images of pop culture icons of the recent past (Omagbitse Omagbemi) swirls and dominates every segment of the stage that she occupies. A dancer (Wendy Perron) clad in a synthetic tutu – trimmed not in delicate ermine but rows of bubble wrap – peers over eyeglasses and scuttles about as if moving in a world that no one else comprehends. Still another (Lily Gold) executes a one-legged skip around the perimeter. A very pregnant woman (Marilyn Maywald) gingerly maneuvers about without eliciting much accommodation from anyone else. A table is dragged across the stage; it reemerges in the finale as Olson climbs atop it and Kinzel sits on the edge with Olson looking somewhat displeased. Jodi Bender, Donna Costello, Kathy Wasik and Shick herself complete the roster.

It’s almost as if these characters are on one side of a subway track, then realize that they’re on the opposite platform from where they need to be. (How many of us have thought we were heading on the Red Line to Shady Grove before discovering that we’ve just boarded the metro to Glenmont which goes thirty miles in the opposite direction?) Sometimes they stop and watch others or lean against the walls at the extremes of the scrim. Shick in a recent posting on the Foundation for Contemporary Arts states that she is “mostly concerned with the utter humanity and vulnerability of dancers” and that she is “haunted by small details”. Unfortunately, this does not automatically translate into compelling choreography, as the overall effect of the multiple dance-scapes occurring simultaneously on both sides of the scrim in “Everything You See” is one of fragmentation. The effect is amplified by the reality that Shick’s movement vocabulary is limited if not secondary to her penchant for quirky poses and gestures, as well as the persistently indeterminate interplay of her dancers.

The proscenium seating also places the audience much closer to the dancers, often a mere foot or two away. This can be disconcerting, as the audience is almost physically drawn into their contortions – the repetitive scoops, swipes, skips and snapping. The “in-your-face” staging may thus enhance a desire on the part of the viewer to turn away or detach. Ironically, this could be Shick’s intention, since the same provocations and responses seem to be occurring among the dancers themselves. The more serene moments for this observer took place when the dancers were positioned closer to the middle of the stage – that is, directly in front of the scrim – providing a little depth of field and less emotionalism. The anatomical body thrusts looked more like choreography.

The sound score by Elise Karmani, from cacophonous band instruments to a crackling fire to country western songs, coupled with frequently mismatched patterns in the costumes designed by Barbara Kilpatrick, contribute to the overarching chaos and anomie.

Copyright © 2014 by Luella Christopher, Ph.D.

Published by IsItModern?